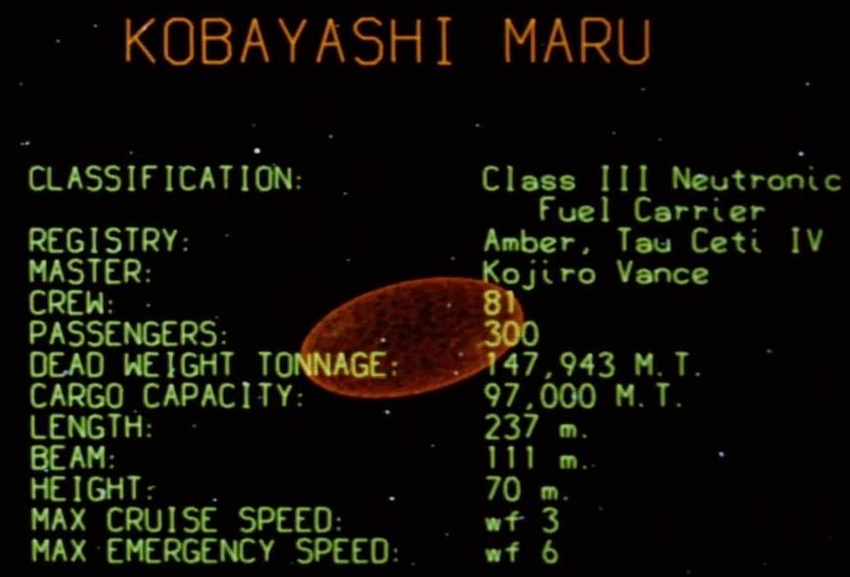

As seen in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, the Kobayashi Maru is a Star Fleet Academy training exercise designed to test the character of cadets. The Maru simulation forces cadets to choose between ignoring a dire request for assistance by a stranded ship (the Kobayashi Maru), or staging a rescue of the ship–despite strong indicators that the distress call is a trap set by an enemy.

The Kobayashi Maru has become part of Star Trek canon, and is often referenced when characters face a “no-win” situation. Think of it as a sort of science-fiction “Catch 22” but with mortal consequences, and you get the idea.

As we creep closer to having our cars and trucks drive themselves, we are forced to consider the Kobayashi Maru, and how operators of self-driving vehicles will be surrendering driving control—and critical decision-making responsibilities—to their cars. More on this in a moment.

Here, I’d like to explore four key hurdles to the mass acceptance and widespread use of self-driving or “autonomous” vehicles. Individually, each of these obstacles represents a bump in the path to hands-free commuting. Collectively, they suggest that our days of playing Candy Crush Saga while being whisked to the office in our own cars may still be a while off—unless another human is driving.

Freaked by the Prospect of Driverless Cars? You’re not Alone

V2V: 260 million cars to bump into

At the moment, cars being operated autonomously are self-contained devices–meaning that all the equipment being used to direct the car or truck is onboard said vehicle.

No current regular-production vehicle should be driven hands free (though there is plenty of footage on YouTube of Tesla drivers doing just that). Part of the reason is that the current semi-autonomous vehicles receive no information from either infrastructure (traffic lights, railroad gates, etc.) or surrounding vehicles.

It’s largely understood that to create a truly autonomous driving environment, public infrastructure will have to play a role. That means that traffic-control devices such as lights and lane-closure indicators will need to transmit status signals to nearby vehicles. At this point in time, the convention for that communication (a wireless transmission protocol along the lines of Bluetooth) is still being developed. We are still very far away from seeing state and local governments spend the money to update systems to accommodate an autonomous environment.

More daunting is the implementation of vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) communication. Just as autonomous cars need to recognize traffic infrastructure information, they also need to communicate with other vehicles. Last year, with the introduction of the redesigned E-Class, Mercedes-Benz became the first vehicle manufacturer to incorporate V2V technology into its vehicles. That’s just one of the 300 or so models available for sale in the U.S.

There are currently an estimated 260 million vehicles on the road in the U.S. Each year 16 to 17 million vehicles are added to the fleet, and roughly the same amount drop out. If every new vehicle were equipped with V2V technology—and we’re a long way away from that point—it would take about 15 years for nearly every vehicle on the road to be so equipped.

Even then, there would be older vehicles not yet retired from service gumming up the works. What impact these cars and trucks would have on an otherwise autonomous-ready fleet is difficult to say, but we can assume that even 15 years from now, pure autonomy will likely be a limited condition.

You can’t break a law that isn’t written yet—or can you?

As of this writing, only 10 states have adopted legislation related to the operation of autonomous vehicles. And in each case, those laws relate to the testing of said vehicles on public roads, not the sale and consumer use of them.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) has begun work on a federal legislative outline, but the guidelines, when completed, are meant to be augmented by regional legislation–which will take considerable amounts of time, research, and dickering, given what we know about most state legislatures.

Here’s the rub: We don’t even know to what extent autonomous driving will be made legal by different cities and states. It’s entirely possible that any number of ruling bodies will hold off on allowing hands-free driving until such time that local authorities deem it safe—or have raised the revenue for any required infrastructure upgrades. For some locales, that time may be years–if not decades–from now.

Atrophy: running before you can walk

Much of the interest in autonomous driving is coming from the tech-savvy and the Millennials. This makes sense, as the traditional automotive media is well stocked with folks who enjoy piloting a vehicle, and they aren’t in any hurry to turn that passion over to Siri, or whatever form of artificial intelligence will eventually take the wheel.

I admire the enthusiasm many folks have for the coming age of driverless driving, but I need to point out two things: First, new drivers probably aren’t going to be allowed to go autonomous until after they’ve logged a considerable amount of real driving time. And secondly, we may need to consider what the impact on our collective driving skills will be if we spend 90 percent of our time in cars not actually driving.

The truth is, no matter how autonomous driving becomes, vehicles will still need to be equipped with a steering wheel, throttle and brake pedals, and full instrumentation. This is because human drivers will still be called upon from time to time to take the controls.

The reasons for this are many. The navigation system may fail; an autonomous-system sensor may go bad. Whatever the reason, we are still going to have to do some actual driving.

The question is, how ready will a world of texting, latte-swilling, Sudoku-solving commuters be to take the wheel? The fact is that driving is a skill, and one that we improve upon with experience. Will taking the wheel only for the occasional jaunt allow our “driving muscles” to atrophy to a dangerous extent?

One possibility is that federal or state laws limit the amount of time a vehicle can be operated in autonomous mode. If limited to, say, 75 percent of the time, vehicle operators would be forced to do their own driving the other quarter of the time–just so they don’t forget how to do so.

Likewise, new drivers may be required to forgo autonomous driving for a number of months—or even years—after receiving their license for the same reason.

While the laws still need to be written, it makes sense that even when fully autonomous driving is available, we may not be allowed to enjoy the hands-free experience all of the time.

Check out all the latest auto show news and reveals

Kobayashi Maru: the no-win scenario

In Wrath of Khan, Admiral Kirk explained that he didn’t believe in the “no-win” scenario. Unfortunately, in the real world, situations arise in which all of the given outcomes are unacceptable, yet one must be chosen.

In driving, it is possible that in the moments preceding a crash, a choice must be made between hitting a school bus, and striking a minivan full of people. Should that very unfortunate situation arise, the driver must select the lesser of two evils.

That decision may be tantamount to deciding who lives and who dies, but no matter the choice, a human made it.

Once we flip the autopilot switch, that no-win decision is being handed over to a computer. Plenty has been written on this topic already, much of which falls under the heading of “autonomous driving ethics.” One MIT paper was ominously titled “Why Self-Driving Cars Must be Programmed to Kill.”

The ramifications of this reality are twofold. First, vehicle manufacturers, insurance companies, and infrastructure providers must come to terms with responsibility for system failure. Ironically, the only party likely to completely duck responsibility in the event of an autonomous-vehicle fatality may be the driver, provided he wasn’t driving at the time of the accident.

This messy interface of liability and responsibility may seriously compromise the extent to which autonomous features may be legally used. It’s possible that laws and/or insurance underwriters will forbid autonomous driving near schools, around parks and playgrounds, in heavy traffic, or even in inclement weather.

Second, expect to see higher insurance premiums for autonomous vehicles—at least in the near term. Those policies will also likely include a number of clauses and conditions limiting when, where, and for how long self-driving systems may be used.

Final Thoughts:

Not unlike a big wedding, which seems like a good idea until the serious planning begins and the couple wishes they had just decided to elope—the road to full vehicular autonomy is long, and far from well marked.

There’s no question that an era of hands-free driving is approaching, and the technology necessary to usher in that era is here or close at hand. But once you mix in laws, liability, and the need for government spending, you realize how far off the dream may be.

Like so many things that seemed cool in the abstract–like call waiting, the Segway, and Dipping Dots ice cream–the reality can be something less than our idealistic projections.

We learn in watching Khan that it was possible to cheat around the no-win scenario, and that Kirk himself had done so as a cadet. We won’t have that option with autonomous cars. We’re going to have to work through the tougher decisions, and that’s going to slow the process down—probably considerably.